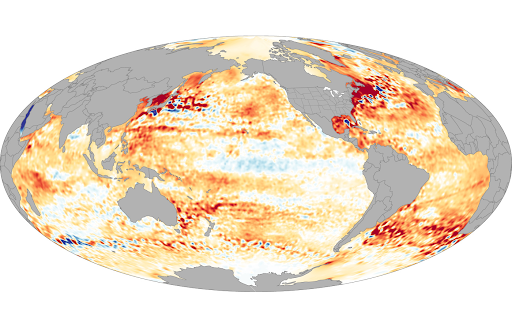

This map shows heat content anomalies (differences from the long-term average)—in the top 700 meters (~2,100 feet) of the global ocean. Positive anomalies mean the ocean gained heat in 2020 (orange); negative anomalies mean the ocean lost heat energy (blue) in 2020. NOAA Climate.gov image, based on data provided by John Lyman (UH JIMAR/PMEL)

Johnson, G.C., and R. Lumpkin (2021): Overview. In State of the Climate in 2020, Global Oceans. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 102 (8), S149–S150, https://doi.org/10.1175/ BAMS-D-21-0083.1.

Johnson, G.C., J.M. Lyman, T. Boyer, L. Cheng, J. Gilson, M. Ishii, R.E. Killick, and S.G. Purkey (2021): Ocean heat content. In State of the Climate in 2020, Global Oceans. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 102 (8), S156–S159, https://doi.org/10.1175/ BAMS-D-21-0083.1.

Johnson, G.C., J. Reagan, J.M. Lyman, T. Boyer, C. Schmid, and R. Locarnini (2021): Salinity. In State of the Climate in 2020, Global Oceans. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 102 (8), S159–S164, https://doi.org/10.1175/ BAMS-D-21-0083.1.

Alin, S.R., A.U. Collins, B.R. Carter, and R.A. Feely (2021): Ocean acidification status in Pacific Ocean surface seawater in 2020. In State of the Climate in 2020, Global Oceans. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 102 (8), S184–S185, https://doi.org/10.1175/ BAMS-D-21-0083.1.

Feely, R.A., R. Wanninkhof, P. Landschützer, B.R. Carter, J.A. Triñanes, and C. Cosca (2021): Global ocean carbon cycle. In State of the Climate in 2020, Global Oceans. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 102 (8), S185–S190, https://doi.org/10.1175/ BAMS-D-21-0083.1.

Tamsitt, V., S. Bushinsky, Z. Li, M. du Plessis, A. Foppert, S. Gille, S. Rintoul, E. Shadwick, A. Silvano, A. Sutton, S. Swart, B. Tilbrook, and N.L. Williams (2021): Southern Ocean. In State of the Climate in 2020. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 102 (8), S341–S345, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-21-0081.1.

The 31st annual State of the Climate report confirmed that several markers such as sea level, ocean heat content, and permafrost in 2020 once again broke records set just one year prior. 2020 was also among the three warmest years in records dating to the mid-1800s, even with a cooling La Niña influence in the second half of the year. New high temperature records were set across the globe.

The report found that the major indicators of climate change continued to reflect trends consistent with a warming planet. The report’s climate indicators show patterns, changes and trends of the global climate system. Notably, carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere also reached record highs in 2020, even with an estimated 6–7% reduction of carbon dioxide emissions due to the economic slowdown from the global pandemic.

Additional examples of the indicators include various types of greenhouse gases; temperatures throughout the atmosphere, ocean, and land; cloud cover; sea level; ocean salinity; sea ice extent; and snow cover. Some notable findings In 2020 include:

-

Sea surface temperatures were near-record high. The globally averaged 2020 sea surface temperature was the third highest on record, surpassed only by 2016 and 2019, both of which were associated with El Niños

-

Global upper ocean heat content was record high from the surface to 700 m (2300 feet) depth in 4 of 5 analyses presented. This record heat reflects the continuing accumulation of thermal energy in the top 2300 feet of the ocean. Ocean heat content was also record high in a deeper layer beneath, from 700 to 2000 m depth. The ocean absorbs more than 90 percent of Earth’s excess heat from global warming. The warmer upper ocean waters can drive stronger hurricanes and increase melting rates of ice sheet glaciers around Greenland and Antarctica.

-

Global sea level was highest on record. For the ninth consecutive year, global average sea level rose to a new record high and was about 3.6 inches (91.3 mm) higher than the 1993 average, the year that marks the beginning of the satellite altimeter record. Global sea level is rising at an average rate of 1.2 inches (3.0 cm) per decade due to changes in climate. Melting of glaciers and ice sheets, along with warming oceans, account for the trend in rising global mean sea level.

-

The ocean absorbed a record amount of carbon dioxide and pH levels continue to decrease. The ocean absorbed about 3.0 billion metric tons more carbon dioxide than it released in 2020. This is the highest amount since the start of the record in 1982 and almost 30% higher than the average of the past two decades. More carbon dioxide stored in the ocean means less remains in the atmosphere, but also leads to increasing acidification of the waters, which can greatly harm or shift ecosystems.

These key findings and others are available from the State of the Climate in 2020 report released online today by the American Meteorological Society (AMS).

The State of the Climate in 2020, led by NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, is the 31st edition in a peer-reviewed series published annually as a special supplement to the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. More than 530 scientists from over 60 countries around the world contributed to the report and reflects tens of thousands of measurements from multiple independent datasets. It provides a detailed update on global climate indicators, notable weather events and other data collected by environmental monitoring stations and instruments located on land, water, ice and in space.

Seven principal investigators from PMEL’s Carbon and Global Ocean Biogeochemistry and Ocean Physics programs co-authored sections in the Global Oceans chapter on ocean acidification, global ocean carbon cycle, ocean heat content and salinity and a section in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean chapter. Dr. Gregory C. Johnson served as the editor for the Global Oceans chapter for the fifth year. As he summarized in the chapter overview.

Over the decades,

seas rise, warm, acidify,

Earth’s climate changes.

Read the full report openly online, NCEI’s high-level overview report is also available online and view , here.