What's New Archive

NOAA recently released the 2019 Arctic Report Card at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting providing updates on the ongoing impact of changing conditions in the Arctic on the environment and communities, especially from continued warming and record sea ice loss. This work brings together 81 scientists from 12 nations to provide the latest in peer-reviewed, actionable environmental information on the current state of the Arctic environmental system relative to historical records.

The average annual land surface air temperature north of 60° N for October 2018-August 2019 was the second warmest since 1900. The warming air temperatures are driving changes in the Arctic environment that affect ecosystems and communities on a regional and global scale.

In the marine environment, August mean sea surface temperatures in 2019 were 1-7°C warmer than the 1982-2010 August mean in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas, the Laptev Sea, and Baffin Bay. Arctic sea ice extent at the end of summer 2019 was tied with 2007 and 2016 as the second lowest since satellite observations began in 1979. The thickness of the sea ice has also decreased, resulting in an ice cover that is more vulnerable to warming air and ocean temperatures. The winter sea ice extent in 2019 narrowly missed surpassing the record low set in 2018, leading to record-breaking warm ocean temperatures in 2019 on the southern shelf. Bottom temperatures on the northern Bering shelf exceeded 4°C for the first time in November 2018. Bering and Barents Seas fisheries have experienced a northerly shift in the distribution of subarctic and Arctic fish species, linked to the loss of sea ice and changes in bottom water temperature.

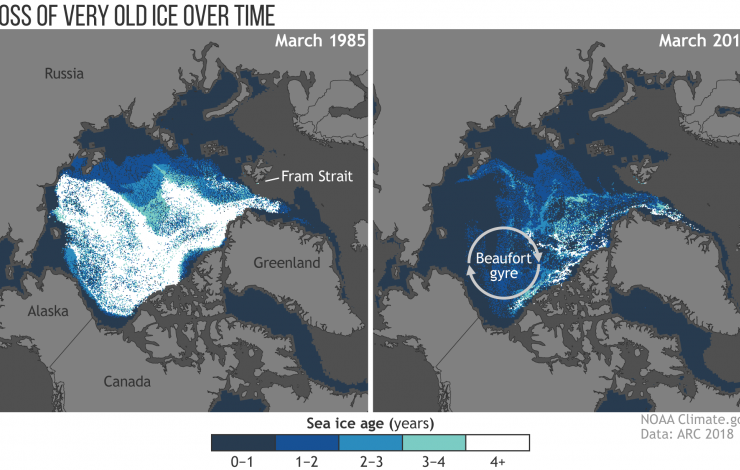

Less than 1 percent of Arctic ice has survived four or more summers In March 1985, sea ice at least four years old made up 33 percent of the ice pack in the Arctic Ocean; in March 2019, ice that old made up 1.2 percent of the pack. Instead, more than three-quarters of the winter ice pack today consists of thin ice that is just a few months old, whereas in the past it was just over half.

PMEL’s Dr. James Overland, Dr. Muyin Wang, Dr. Kevin Wood, and Dr. Carol Ladd contributed to sections on surface air temperature, sea ice and sea surface temperatures.

Read more highlights and the full Arctic Report card here.

The NOAA Press Release can be found here.

International team assesses widespread effects of polar warming

With 2019 on pace as one of the warmest years on record, a new study published today in the journal Science Advances, reveals how rapidly the Arctic is warming and examines global consequences of continued polar warming. The study reports that the Arctic has warmed by 0.75oC in the last decade alone. By comparison, the Earth as a whole has warmed by nearly the same amount, 0.8oC, over the past 137 years.

“Many of the changes over the past decade are so dramatic they make you wonder what the next decade of warming will bring,” said lead author Eric Post, a UC Davis professor of climate change ecology. “If we haven't already entered a new Arctic, we are certainly on the threshold.”

What 2 degrees global warming means for the poles

The comprehensive report represents the efforts of an international team of 15 authors specializing in an array of disciplines, including the life, Earth, social, and political sciences. They documented widespread effects of warming in the Arctic and Antarctic on wildlife, traditional human livelihoods, tundra vegetation, methane release, and loss of sea- and land ice. They also examined consequences for the polar regions as the Earth inches toward 2oC warming, a commonly discussed milestone.

“Under a business-as-usual scenario, the Earth as a whole may reach that milestone in about 40 years,” said Post. “But the Arctic is already there during some months of the year, and it could reach 2oC warming on an annual mean basis as soon as 25 years before the rest of the planet.”

The study illustrates what 2oC of global warming could mean for the high latitudes: up to 7oC warming for the Arctic and 3oC warming for the Antarctic during some months of the year.

The authors say that active, near-term measures to reduce carbon emissions are crucial to slowing high latitude warming, especially in the Arctic.

Beyond the polar regions

Major consequences of projected warming in the absence of carbon mitigation are expected to reach beyond the polar regions. Among these are sea level rise resulting from rapid melting of land ice in the Arctic and Antarctic, as well as increased risk of extreme weather, deadly heat waves, and wildfire in parts of the Northern Hemisphere.

“What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic,” said co-author Michael Mann, a distinguished professor of atmospheric sciences at Penn State. “The dramatic warming and melting of Arctic ice is impacting the jet stream in a way that gives us more persistent and damaging weather extremes.”

Muyin Wang, research meteorologist with the University of Washington Joint Institute for the Study of the Ocean and Atmosphere and NOAA PMEL is a co-author of the research. Other institutions include Pennsylvania State University; Aarhus University; University of Oxford; University of Lapland; University of Colorado, Boulder; Chicago Botanic Garden; Dartmouth College; Umea University; University College London; U.S. Arctic Research Commission; and Harvard University.

Funding for the study was provided by grants from the U.S. National Science Foundation, Academy of Finland and JPI Climate, National Geographic Society, Natural Environment Research Council, the Swedish Research Council, U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and NOAA.

Originally posted on UC Davis on December 4, 2019.

A mosaic of young sea ice captured during a flight campaign over the Chukchi Sea launching various atmospheric and oceanographic probes and floats.

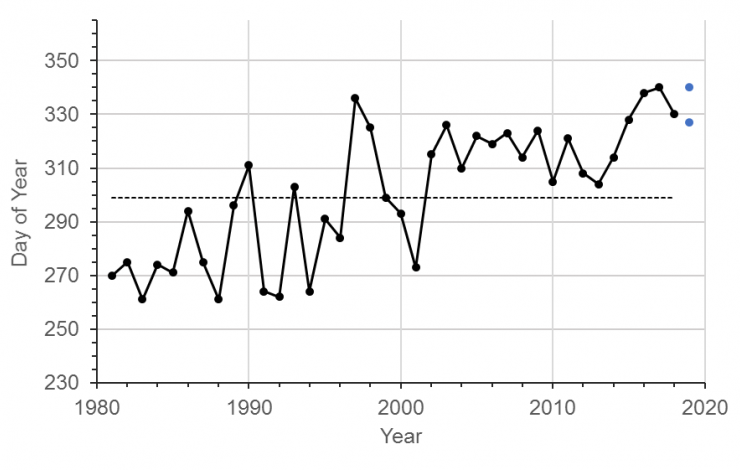

The black dots show the observed day of year that sea-ice concentration in the reference area northwest of Icy Cape first reaches 30%, as determined from passive microwave data. The blue markers show the range (14 days) of the projected onset of freeze in 2019. The dashed line shows the long-term mean (1981-2016).

PMEL has released an experimental annual freeze-up projection for the Chukchi Sea continental shelf northwest of Icy Cape. The freeze onset is projected to begin between 23 November and 6 December 2019. This is 28-41 days later than the long-term average (1981-2016). At freeze-up in 2019, sea-ice in the northwest of Icy Cape will consist entirely of thin, newly formed types (e.g. sheets and thin pancake), especially near the coast. For this projection, the onset metric is defined by sea-ice concentration reaching 30% as determined by passive microwave observations collected in the area around Icy Cape in the Chukchi Sea.

The data considered in this projection includes observations collected from autonomous ocean profiling floats, aircraft and satellite-derived visible imagery, and SST radiometry in 2016, 2017, 2018 and 2019. Persistence of sea ice was evaluated using historical ice concentration data from passive microwave satellites, provided by the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC).

The purpose of this experiment is to develop an informed basis for advising a hypothetical maritime interest operating in the region and to identify conditions that cause sudden large departures (increase in risk). It also provides a result that can be evaluated against other methodologies. Data from various technologies deployed during the Arctic Heat flight campaigns help to fill in data gaps in the Arctic and determine limiting factors in projecting sea ice freeze up in hopes of improving seasonal model forecasts.

Read the full projection and rationale here: https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/arctic-heat/projected-onset-freeze-chukchi-sea-continental-shelf-2019

Learn more about the work being done on the Arctic Heat page: https://www.pmel.noaa.

PMEL is excited to host seven undergraduates this summer from across the United States! They are working across various research groups studying ocean carbon, Madden-Julian oscillation impacts, meteorological data from Station Papa, fisheries-oceanography research in the Bering Sea, acoustic data from the Ross Sea, and ELLIE. The students are supported through NOAA, University of Washington’s Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean (JISAO) internship program, and Oregon State University’s Research Experience for Undergraduates.

Harrison Knapp is a NOAA Hollings Scholar working with Dr. Chidong Zhang on assessing the influence of the Madden-Julian Oscillation on snowpack in the Western United States. He is currently a student at the University of Southern California pursuing both a B.S. in GeoDesign and a B.A. in Earth Sciences.

Sam Mogen is a NOAA Hollings Scholar working with Drs. Jessica Cross and Darren Pilcher on exploring oxygen cycling in the Bering Sea using the Bering 10K model. He is a student at the University of Virginia studying environmental science and global studies.

Madeline Talebi is a JISAO intern working with Drs. Meghan Cronin and Nick Bond on finding and interpreting archived meteorological data from Station Papa Ocean Weather Ship between December 1949 and 1981. She is currently studying Chemical Engineering at the University of California, Irvine.

Isabelle Chan is a JISAO intern working on decreasing the degree of uncertainty between water vapor and carbon dioxide measurements with Dr. Sophie Chu. She is currently studying Environmental Science with an emphasis in Conservation at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington.

Leo MacLeod is a undergraduate at the University of Washington working with Dr. Carol Ladd on fisheries-oceanography research in the Bering Sea.

Ellie Lee is a JISAO intern working with Dr. Carol Stepien in the Genetics and Genomics Group.

Miriam Hauer-Jense is working with Drs. Bob Dziak and Joe Haxel on analyzing data from the Ross Sea hydrophones for marine mammals through Oregon State University’ Research Experience for Undergraduates program. She is a sophomore at Scripps College.

Read more about each of them and their projects here.

On May 16, six saildrones loaded with scientific instruments and cameras launched from a dock in Alaska's Dutch Harbor to monitor ongoing changes to the U.S. Arctic ecosystem food-chain, ice movement, and large-scale climate and weather systems.

This is the first year NOAA and NASA scientists will be working together to use the drones to survey as close to the Arctic ice edge as possible. Measurements collected this summer in the Arctic will not only be used to improve NOAA and NASA satellite ocean temperature measurements, they will also be available to global weather agencies for operational use.

While most of the saildrones will be pursuing the ice edge for the duration of the three-month mission, two other simultaneous projects will also tackle some big questions on how this cutting-edge technology can be used to collect critical observations. NOAA PMEL scientists will continue to study how the Chukchi Sea is absorbing carbon dioxide to help improve weather and climate forecasting as well as our understanding of ongoing changes in the Pacific-Arctic ecosystem. The Bering Sea is home to the largest walleye pollock fishery and the declining population of northern fur seal which primarily feed on pollock. During the summer, NOAA Fisheries scientists will use the saildrone combined with traditional at-sea tracking techniques and video cameras to get a seals-eye view during fur seal feeding trips and measure walleye pollock abundance and distribution. Read more about the work done by NOAA's Alaska Fisheries Science Center.

This is a joint NOAA mission along with the Earth & Space Research, the University of Washington's Joint Institute for the Study of Ocean and Atmosphere and the Applied Physics Lab, and Saildrone, Inc.

Saildrones have traveled about 45,000 nautical miles on Arctic missions since 2015. Follow along with drones as they collect data on fish, fur seals, changes in the Arctic ecosystem and more on the mission blog.

These maps show the age of sea ice in the Arctic ice pack in March 1985 (left) and March 2018 (right). Less than 1 percent of Arctic ice has survived four or more summers. See more visual highlights of the Arctic Report Card on NOAA climate.gov

December 11 - NOAA released the 2018 Arctic Report Card at the American Geophysical Union fall meeting in Washington, D.C today bringing together the work of 81 scientists from 12 nations to provide the latest in peer-reviewed, actionable environmental information on the current state of the Arctic environmental system relative to historical records.

The Arctic continued it long-term warming trend in 2018, warming at twice the rate relative to the rest of the globe with Arctic air temperatures for the past five years (2014-18) exceeding all previous records since 1900. Arctic sea ice in 2018 remained younger, thinner, and covered less area than in the past. The 12 lowest extents in the satellite record have occurred in the last 12 years. In the Bering Sea, winter sea ice extent reached a record low for virtually the entire 2017-2018 ice season, which typically begins to form at the beginning of October, expands through the winter and then melts through the spring. During two weeks in February, typically the height of winter, the Bering Sea lost significant ice cover, about ~215,000 km2 or about the size of Idaho. Ocean primary productivity levels in 2018 were sometimes 500% higher than normal levels in the Bering Sea which is linked to the record low sea ice extent in the region. The Bering Sea is an important commercial fishing region and supports a vibrant sea ice-ecosystem with abundant seals, birds, and other pelagic species that critically depend on the timing of sea ice formation and retreat.

Continued warming of the Arctic atmosphere and ocean are driving broad change in the environmental system in predicted and, also, unexpected ways. New emerging threats are taking form and highlighting the level of uncertainty in the breadth of environmental change that is to come. For more details, visit the Arctic Report Card website: https://arctic.noaa.gov/Report-Card

PMEL’s Dr. James Overland and Dr. Muyin Wang co-authored the surface air temperature essay and Dr. Carol Ladd co-authored the sea surface temperature essay.

Read the NOAA Press Release here.

Watch the video highlights on YouTube here

Seasonally ice-covered marginal seas are among the most difficult regions in the Arctic to study. The scarcity of observing systems in these areas also hinders forecast services in the region and is a major contributor to large uncertainties in modeling and related climate projections. The Arctic Heat Open Science Experiment strives to fill this observation gap with an array of innovative autonomous floats and other near real-time weather and ocean-sensing systems that allow for continuous monitoring of changing conditions in the Chukchi Sea. Since 2016, over 1,000 Arctic Ocean profiles have been collected by the Arctic Heat project and transmitted in real-time via the Global Telecommunications System (GTS). Data collected during the 2017 field season showed particular warmth in the lower ocean which was a leading factor for the record late freeze up (1 month later than usual) in the region and likely would not have been detected without this field campaign. This event caused a ripple effect including impacts on whale migration patterns, physical ocean circulation patterns and subsistence hunt practices that depend on ice.

This week, researchers aboard the NOAA Twin Otter are launching various atmospheric and oceanographic probes and floats as part of the third and final flight campaign of 2018. They will launch an Air-Launched Autonomous Micro-Observer (ALAMO) profiling float and 20 Airborne eXpendable BathyThermographs (AXBT) and carry out a set of low level surveys around the R/V Sikuliaq using LIDA, longwave radiometry, and themrla imaging. They will also be on the lookout for higher wind/wave situations to collection additional data for NASA's Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite (ICESat) 2 which will be launched on September 14.

Arctic Heat is an open science experiment, publishing data generated by the project to further NOAA's Science Missions with real-time data to facilitate timely observations for use in weather and sea-ice forecasts, to make data readily accessible for model and reanalysis assimilation, and to support ongoing research activities across disciplines.

This mission is in coordination with the Office of Naval Research (ONR)'s Stratified Ocean Dynamics of the Arctic (SODA) in response to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy's "Interagency Research Effort To Improve Weather, Ice, and Water Forecasting in the Arctic Ocean" led by ONR, NOAA, National Science Foundation, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and NASA. Arctic Heat is a joint effort of NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (PMEL) Arctic Research, the Innovative Technology for Arctic Exploration (ITAE) program, the ALAMO development group at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), and the Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean (JISAO) at the University of Washington.

International Annual State of the Climate Report Finds 2017 was One of Three Warmest Years on Record

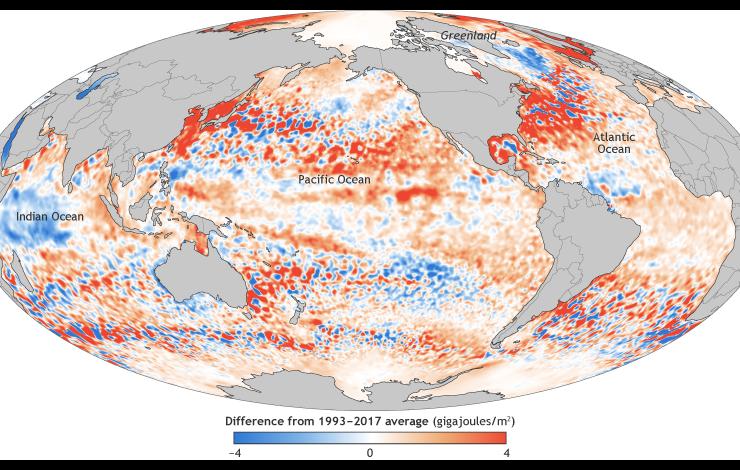

This map shows the ocean heat content in the upper ocean (from the sea surface to a depth of 700 meters, or 2,300 feet) for 2017 relative to the 1993–2017 baseline. It's based on a combination of Argo float observations and satellite data. Places with higher-than-average heat storage are orange, while places with lower-than-average heat storage are blue

The 28th annual State of the Climate report was recently released highlighting that 2017 was the third-warmest year on record for the globe, behind 2016 and 2015. The new report confirmed that 2016 surpassed 2015 as the warmest year in 137 years of recordkeeping. Several climate indicators also set new records, including greenhouse gas concentrations, sea level rise, heat in the upper ocean, and Arctic sea ice extent.

The 2017 average global CO2 concentration was the highest measured in the modern 38-year global climate record and records created from ice-core samples dating back as far as 800,000 years. Sea level rise also hit a new high, about 3.0 inches higher than the 1993 average and rising globally, at an average rate of 1.2 inches per decade. Heat in the upper ocean hit a record high, reflecting the continued accumulation of thermal energy in the uppermost 2,300 feet of the global oceans. Arctic sea ice maximum extent (coverage) was the lowest in the 38-year record. Extreme precipitation was also recurring theme this past year.

Surface fluctuates,

ocean warms more steadily,

seas continue rise.

The State of the Climate in 2017 was recently published in a special edition of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. This report is led by NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information and is based on contributions from more than 500 scientists representing over 65 countries around the world. It is the most comprehensive annual summary of Earth’s climate and provides a detailed update on global climate indicators, notable extreme weather events and other environmental data collected from locations on land, water, ice, and in space.

Principal investigators from PMEL’s Carbon, Arctic and Large Scale Ocean Physics programs contributed to sections on the global ocean carbon cycle, ocean heat content and arctic air temperature. Dr. Greg Johnson served as the editor for the Global Oceans chapter for the third consecutive year.

Access the full BAMS State of the Climate in 2017 report here.

Over the last week, Saildrone Inc. and NOAA have launched the first batch of saildrones in Alaska and the Washington coast to enhance our understanding of fisheries, ocean acidification and climate science.

Four of these saildrones launched from Dutch Harbor, Alaska this past weekend and will make their way northward, surveying more than 20,000 miles through Bering Strait and into the Arctic Ocean to measure atmospheric and surface ocean conditions, carbon dioxide in the ocean, and the abundance of Arctic cod. Arctic cod is a key component of the Arctic marine ecosystem as a food source for seabirds, ringed seals, narwhals, belugas and other fish. These two missions will gather measurements to identify ongoing changes to the Arctic ecosystem and how changes may affect the food-chain as well as large-scale climate and weather systems.

Last year was the first time the drones journeyed through the Bering Strait into the Arctic with a newly adapted system to measure carbon dioxide concentrations. Jessica Cross, NOAA Oceanographer at PMEL, continues to use saildrones to study how the Arctic Ocean is absorbing carbon dioxide to help improve weather and climate forecasting and our understanding of ocean acidification in these critical ecosystem areas.

Alex De Robertis, NOAA Fisheries Biologist with Alaska Fisheries Science Center, is mapping fish with sound to determine the amount and distribution of Arctic cod. Two drones will survey the same remote locations as previous ship-based surveys in hopes of demystifying the story of Arctic cod as temperatures and ice cover change in the Arctic. “We are trying to unravel the puzzle of what happens to the young Arctic cod that are so abundant in the summer on the Chukchi shelf,” says De Robertis. “There are many young-of the year Arctic cod in this area, but comparatively few adults. They either move to other areas or don’t survive the winter. What is their fate?”

These two missions will continue to further demonstrate the operation of these platforms at high-latitudes through the first fully autonomous acoustic fish survey and field tests of an updated carbon dioxide system that was re-designed to address challenges observed during the 2017 mission.

NOAA and Saildrone, Inc. are embarking on the fifth year of collaboration and novel data collection using saildrones to better understand how changes in the ocean are affecting weather, climate, fisheries and marine mammals.

Read more about all the NOAA Saildrone missions this summer here: http://www.noaa.gov/stories/flotilla-of-saildrones-deploy-to-artic-and-pacific-for-earth-science-missions

Follow along with the Arctic missions on this blog: https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/itae/follow-saildrone-2018

Read more about the West Coast Fisheries survey here: https://swfsc.noaa.gov/news.aspx?ParentMenuId=39&id=23090

Learn more about what we did in previous Alaska surveys:

PMEL Follow the Saildrone 2017

NOAA Fisheries video on 2017 mission

2017 Fur Seal Blog by Carey Kuhn

NOAA Saildrone Research 2016 – Live YouTube Broadcast Recording

2016 Press release and Press Conference

Tracking Technology: the Science of Finding Whales: Video interview with Jessica Crance

2016 Fur Seal Blog by Carey Kuhn

Congratulations to all involved with the 2016 Saildrone missions on receiving the Department of Commence Bronze Award and to Susie Snyder for receiving the NOAA Distinguished Career Award.

NOAA’s PMEL and Alaska Fisheries Science Center were awarded the Bronze Medal for “strengthening NMSF-OAR collaborations through the pioneering use of a Saildrone for next-generation ecosystem surveys in the Bering Sea”.

In 2016, the team successfully conducted the first ecosystem study using two Saildrones. The mission combined both physical and biological oceanography to seek out new ways to supplement traditional vessel-based research. The Saildrones each traveled almost 3,000 nautical miles in the 101 day mission testing innovative technologies, including a specially developed echo sounder and a modified whale acoustic hydrophone. Collectively, the oceanographic, meteorological, and fisheries measurements provided unique and groundbreaking insights to understanding the economically and culturally important ecosystem in the Bering Sea.

This was a collaborative mission between the NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Lab, NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center, UW Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean, Saildrone Inc., Simrad AS/Kongsberg Maritime, Greeneridge Sciences Inc, and Wildlife Computers. Read more about the 2016 mission here.

The DOC Bronze Award is the highest honor award granted by the Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere, which recognizes superior performance characterized by outstanding or significant contributions, which have increased the efficiency and effectiveness of NOAA.

Susie Snyder was also awarded The Distinguished Career Award for her “continued efforts in improving budgetary policies and procedures relating to memorandum of agreements and reimbursable funds throughout 30 years of service to NOAA”. This award honors contributions on a sustained basis — a body of work — rather than a single, defined accomplishment. This award also recognizes significant accomplishments across all NOAA program areas and functions that have resulted in long- term benefits to the bureau’s mission and strategic goals.